If ever there was a company town, Stratford-upon-Avon is that town. William Shakespeare was born here and he died here. He married here, had three children who lived and died here. He owned LOTS of property here, became Stratford’s most prominent citizen, and is buried (with his entire family) beside the high altar in the local church. So, really—although he does belong to the world—no other town can claim him as Stratford does.

We have been coming here, off and on, for some years to pig out on plays at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. Only on one visit did we see just one! This visit we treated ourselves to three wonderful productions—two excellent and one so phenomenal that it will define the play for me forever. The two were the Jacobean revenge tragedies The Witch of Edmonton (1621) by Dekker, Rowley, Ford, (and maybe some others) and The White Devil (1612) by John Webster. The other play was Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing (1598), here produced as Love’s Labours Won. Much Ado is my favorite comedy, bar none, and I’ve seen it dozens of times. This version left both of us absolutely breathless.

In between plays, we enjoyed Stratford. We stayed at the White Swan (again), parts of which date back to 1450. So, you eat and drink in the front part with its ancient oak beams, low ceilings, and sagging walls, while you stay and sleep in the comfortable modern new section of the hotel that’s off the back of the building. So, we wandered around Stratford, took a river cruise, had an excellent walking tour of the town, and ate in some good restaurants. I said that Stratford was a company town, and Shakespeare is the product. Shops and restaurants reference his plays, sometimes nonsensically—Iago’s is a jewelers’ store (Honest Iago?), Othello’s is a restaurant, Romeo and Juliet are everywhere. The town is beginning to advertise that it’s “Not Just Shakespeare,” but his birthplace, gravesite, and, most of all, his plays are what draw 3 million visitors a year to a town now the size of Newport.

The two Jacobean plays—The Witch of Edmonton and The White Devil—were part of a season’s theme the RSC called “The Roaring Girls.” They scheduled a season of classic dramas about women, women who challenged the feminine stereotype of the day by seizing some kind of power, even illicit or criminal power. In the case of The Witch, wonderfully played by the great Eileen Atkins, an old woman who is abused, blamed for misfortunes, and accused of witchcraft by men in the town, finally wishes that she were a witch indeed and makes a pact with the devil, who grants her wish. The devil (who was brilliant in his black body suit and shining red eyes) appears to others only as a dog and causes no end of havoc. In the case of White Devil, a woman trying to raise the fortunes of her family becomes the evil adviser to a duke. She pimps her sexy sister to become his mistress, setting in motion the murders of her sister’s husband and the duchess. When her own honest brother is an obstacle to her plans, she coldly murders him. Of course, it being Jacobean revenge tragedy, the stage was absolutely littered with dead bodies and globs of gore were flung everywhere! I resolved never again to sit in the front row at the Swan Theatre, although the worst that hit us was simply champagne.

Anyway, what caught my attention in these strong women themes was that the women “g0t what was coming to them.” They paid an awful price for stepping outside the bounds of the 17th century definition of feminine. Mother Sawyer (the witch) is sentenced to hang and is (as was historically accurate) executed. But she also loses her soul to the devil and none of the characters forgive her. The worst she has done is make cows stop giving milk and fields go dry. In the subplot of the play, a young man gets a girl pregnant, marries her, then marries another girl for her dowry, then MURDERS her (while her pure soul goes to heaven). While he is convicted and sentenced to hang like Mother Sawyer, all the other characters forgive him and he dies repentant so gets God’s forgiveness as well. HIS soul goes to heaven, while the poor witch spends eternity in hell.

In The White Devil, all the women are knifed at the end—ambitious adviser, sensuous mistress of the duke, kind friend and lover alike—sliced and diced and dumped in a heap. Simultaneously. Like the witch (who does not go out silently), these women have major death scenes that allow them to bewail how bad it all is for women. But they all still lose everyone’s sympathy, including that of the audience. The politically opposing count with all his henchmen survives everybody, with a lot of blood on his hands. So women get punished for ambition. Men are rewarded with power.

I had to compare this with Shakespeare. He has such strong women in his plays and some of them, too, are criminal or over-reaching—think Lady Macbeth or Cleopatra. But Shakespeare always creates them with such three-dimensionality that we always feel some sympathy for them. I thought again how incredibly generous a writer he is with “outsider” characters—Shylock or Othello, say—characters that in any other playwright of his day would have been conventional, stereotypical, and lacking any sympathetic motive. Also, these Jacobean plays were produced after Shakespeare, as much as twenty years after a play like Much Ado was first produced. Yet they don’t seem to have learned anything from him. There’s nothing like the rhythm of a Shakespearian play with these guys—no alternating a comic moment with a tragic action or vice versa. Their transitions clunk. And one is forever asking, “Wait! Who’s that?” whereas Shakespeare prepares for every entry and introduces every character without you being aware of it.

Thus, to this RSC production of Much Ado About Nothing. It was set in 1918, as if the returning soldiers came back at the first Christmas after the war to a large country house in England that was serving as an officers’ hospital. This pulls it into this year’s theme, which is World War I, but the late Edwardian (early George V) atmosphere really worked. It allowed for vibrant uniforms, gentlemen’s rituals like billiards, live drawing room music, church hymns, choirs, dancing, and all the protocol of the Edwardian age that comfortably reflected the themes of the play. The production was brilliant. Every bit of stage business served the script. The language was delivered as purely as a crystal bell, every word clear, parsed to exactitude (this is a hallmark of the RSC). The director, Christopher Luscombe, milked comic moments out of lines I had never considered funny before. The Dogberry character was a revelation, pompous, hysterical with malapropisms, then suddenly pitiable. Much of the dialogue was absolutely gut-splitting. The audience were beside themselves. Best of all, Benedict and Beatrice (each performance stunning in itself) were completely balanced. So often one or the other is outstanding (like David Tennant or Emma Thompson) but they aren’t perfectly matched by their counterpart (in my humble opinion). This couple, Edward Bennett and Michelle Terry, were perfect. From the first minute, they deserved each other and their happiness. The entire play was a wonder.

- Cruising on the River Avon at Stratford

- Royal Shakespeare Theatre in the background on the banks of the Avon. Roger in shirtsleeves on Halloween when the temperature was around 65 F.

- The back of the RSC main stage from the river

- Holy Trinity Church from the river.

- All Soul’s Day, November 1st, and I’m in a tee-shirt! The White Swan hotel is behind me.

- Lady Macbeth

- Prince Hal

- Hamlet

- Falstaff

- David, our walking tour guide, outside the RSC main entrance. Totally restored inside and reopened in 2010, it seats 1,060. There’s a deep thrust stage with capacity for raising additional platforms onstage.

- The Swan Theatre, a galleried house with a deep thrust stage.Seats 461. It connects inside with the RSC Theatre.

- This pub, “The Black Swan, “is the favorite hang-out of RSC actors after the show. Canadians during WWII called it “The Dirty Duck” and, depending on which direction you approach, it’s one or the other.

- Looking down the Avon towards the bridges.

- Looking up the Avon towards Holy Trinity Church.

- At the end of his life, fabulously wealthy from his ownership of successful London theaters (not by being a playwright–tho’ his plays filled his theaters), Shakespeare retired to Stratford and became lay rector of Holy Trinity, the church where he was baptized, married, and would be buried.

- The entrance to the nave. Shakespeare was very generous to his church–giving 470 pounds in a time when the vicar made 12 pounds a year in salary.

- Well, it was Halloween weekend.

- The nave of the church.

- Back down the nave from the transept. There has been a church on this spot since about 550.

- Clopton Chapel.

- Clopton Chapel, family contemporary with the Shakespeares.

- The “American Window” was a gift from the American ambassador in 1896. The lowest panels depict the arrival of the Pilgrims in the New World.

- The chancel, looking at the high altar. Shakespeare, his wife, and his daughter and family are buried right by the altar. This BEST spot in the church was reserved for him–not because he’s the world’s greatest playwright–but because he was so wealthy and so generous to the church. Money speaks louder than poetry!

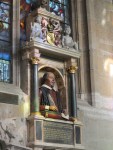

- The placement of the Shakespeare monument.

- This bust of Shakespeare was created and placed her during the lifetime of his wife and two daughters. Thus, we can assume that it really resembles him.

- The bust and the graves beneath of Anne and William Shakespeare.

- Good friend, for Jesus’ sake forbear/To dig the dust enclosed here/ Blessed be he who spares these stones/And curst be he who moves my bones.

- The graves of John and Susanna Hall, who was the daughter of William and Anne Shakespeare.

- This Bible dates from Shakespeares’s lifetime and would have been chained to the lectern.

- Shakespeare’s son, Hamnet (aged 11), is likely buried in the churchyard.

- Holy Trinity Church.

- The home of Susanna and John Hall. He was a prosperous physician.

- On this spot stood New House, Shakespeare’s grand home at the end of his life. He died here. He owned not only this house, but a farm and several orchards. And gave extensively to his church.