We have just passed the halfway point of our British portion of Roger’s sabbatical. Suddenly, we both have the sense of the time flying by and the intensity of our schedule increasing tremendously. We realize that we are double-timing—trying to fit in all the university/consulting options for Rog and to see all the family and friends as well. So far, so great! But there are days when one or the other of us feels completely out of breath.

This past weekend was spent (well spent!) with our Simpson family relatives. Gillian, Roger’s little sister, is a teacher and this week is half-term holiday. So we joined her and her husband Dominic and her younger son, Matt (also a teacher on half-term) in visiting her older son, Ed, and his wife Claire in their new house just outside of Oxford.

It was such a warm, comfortable visit, with the leisure to sit and talk for hours. I’ve never had the luxury of such long, in depth conversations with my nephews, now grown to be these wonderful young men, so full of ideas and exciting futures. It is a delight to get to know Claire better. She is one of a very few women engineers working on the aerodynamics of Formula-One cars, presently working for Mercedes Benz. The men watched both British football and American.

We wandered around Oxford to see Said Business School, where Edward works, and also the old beautiful colleges of the university. Said is especially interesting in a place like Oxford. The story is that Said, the donor, wanted to give mega-megabucks to Oxford to found a business school and they turned him down! It was felt that “business” wasn’t the right fit with Oxford’s esteemed intellectual identity. When at last Mr. Said’s munificence was accepted, they insisted that the school be built across the canal from the original colleges. I don’t know if this is an urban legend or at least partly true. I’ve heard it from several sources, so there might be some substance to it! At any rate, the school is hugely successful, very contemporary, and very impressive. It is so new that rooms still smell of new wood.

We wandered the town, in and out of buildings out of history and legend and went out to a great pub in the evening. Sunday we visited Blenheim Palace, the seat of the Spencer-Churchills, the Dukes of Marlborough. Blenheim was a reward to John Churchill for winning the Battle of Blenheim in 1704 and is one of the grandest palaces in England. The 11th Duke had died about 10 days before and our visit day was, fortunately, the first day that the palace had been reopened to the public after the funeral and mourning period. Blenheim, as all Newporters know, was restored in the late 1890s and at the turn of the 20th century, with the $10 million dowry of Consuelo Vanderbilt when she was married off to the 9th Duke of Marlborough in one of the biggest “cash for title” deals in Gilded Age history. It was not a happy match. But I enjoyed the three lovely portraits of Consuelo as the 9th Duchess that hang in the house.

At the other end of the art scale, there was an exhibition of installations inside Blenheim by Ai Weiwei, the dissident Chinese artist. The exhibits were startling and certainly kept one’s attention. Sea crabs scuttled around in apartments elegantly furnished with 18th century chairs and portraits. Gilded beasts leered at the formal dining table settings. Photographs of every iconic site for global tourists were hung askew and punctuated down the center with a FU middle finger. It was all deeply, and obviously, subversive of everything Blenheim stood for—of the “meaning” of Blenheim Palace. What astounded me wasn’t the installations themselves—it was trying to figure out who on staff at this monster 18th century monument to power and aristocracy would give permission? invite? an artist like Weiwei to create tableaus that undercut the Blenheim experience in such an amazing way. We kept saying to each other: “Don’t they get it?”

We feasted that evening back at the house on the traditional roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, possibly the very best part of a great day.

Our journey back took us the long way through London to Greenwich, and we were very glad we had Matt in the car with us to navigate! While he took off to his college to catch up on classroom work, we were able to see our niece Charlotte and her little son, Oscar, who comes up in a few days on his first birthday.

By the time we got back to Cranleigh, we were in need of laundry and sleep. But we are off again tomorrow . . .

- Said School of Business at Oxford University. My nephew, Ed Simpson, now works here. The very modern architecture still reflects the traditions of the old Oxford colleges. Eg. The “dreaming spire” is interpreted by a ziggurat.

- The usual interior quad of a college reinterpreted in very contemporary fashion.

- Ed and Gill Simpson, his mum and Roger’s youngest sister.

- There’s an open amphitheater on the roof. You can see some of the original spires of Oxford in the distance.

- The ziggurat from the amphitheater.

- Ed and his uncle, Roger

- The graduate student lounge.

- The patron saint of the business school, Margaret Thatcher.

- One of the lecture theaters.

- Rog and me with Ed.

- Bullish on the new business school.

- Oxford canal.

- Wandering through Worcester College.

- The Ashmolean Museum, oldest in the world

- Martyrs monument to the bishops burned at the stake by Henry VIII.

- Bikes everywhere.

- Sheldonian Theatre, built by Christopher Wren, 1664-1668.

- Inside the Bodleian Library, founded 1598, opened 1602. Ground zero of libraries in the English-speaking world.

- The Bodleian.

- Me and Thomas Bodley

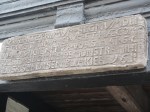

- Roger at the original entrance to the “Astronomy and Rhetoric” collection.

- The Radcliffe Camera, mid-1700s

- Rog and me with Ed and his wife, Claire

- Roger, his sister Gillian, Claire and Ed

- The Church of St. Mary the Virgin. Claire was baptized here.

- The Examination Schools where everyone takes all examinations.

- Going into Magdelen College, mid-15th century

- Roger with his nephews, Ed and Matt Simpson.

- The list includes Stephen Hawking, Oscar Wilde, Elizabeth Taylor, Margaret Thatcher, Thomas Hardy, Lawrence Fox, Ben Kingsley, and many others

- Once called The Spotted Cow, this tavern was renamed since it was a center for horse race gambling and you met your “turf accountant” here over a pint.

- A pint at the Turf Tavern, 1381.

- Street names are delightful.

- Punters on the River Isis (actually part of the Thames)

- and Gill and Claire–and me.

- The gastro-pub where we ate that evening.

- From the left: Dominic and Gill Simpson, Matt, Claire, Ed, Eileen and Roger. An excellent meal!

- On the Sunday we had a great day out at Blenheim. This was the first day the estate had reopened following funeral services for the 11th Duke of Marlborough.

- Blenheim Palace was the reward John Churchill (1st Duke of Marlborough) received for winning the Battle of Blenheim in 1704. John Vanbrugh began building it in 1705 to 1716.

- Vanbrugh was probably a better playwright than architect. This massed baroque is really severe and monumental.

- Entering the Great Hall at Blenheim.

- One of the family salons.

- Here are two Newport girls: me with Consuelo, 9th Duchess of Marlborough (nee Consuelo Vanderbilt).

- These are the Newport connections. Here is the 9th Duke of Marlborough.

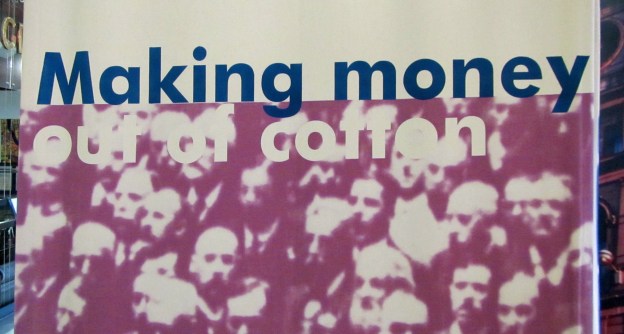

- The beginning of the Ai Weiwei exhibition. Certainly, an attention-getter! Here are thousands of plastic crabs washed up on an Aubusson carpet in one of the grandest salons.

- This is formed by the joining of many three-legged stools. It so clashes with the room.

- Here in the formal dining room, all these gilded beasts look on.

- Under Consuelo’s portrait, along with all the formal furnishings, these odd, white chairs.

- A big bowl of ceramic beads in the center of the room.

- In the library, Queen Anne who gave Blenheim to the first Duke of Marlborough.

- Back to Weiwei, these many photographs lining the bookcases were certainly less cryptic than the other installations.

- Photographs of the iconic tourist places of the world were mounted sideways and shot with a middle-finger gesture.

- What made me very curious was the question: Who at Blenheim authorized an installation that was so subversive to everything that Blenheim stands for? Didn’t they get it?

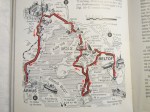

- Map of China.

- The library was designed by Christopher Wren

- The organ in the library.

- The Marlborough family chapel. The scent of flowers from the funeral arrangements was overwhelming!

- The tomb of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough and his Duchess, Sarah.

- More Weiwei outside.

- Our gang with Weiwei.

- Landscaping by Capability Brown, c. 1770s.

- My nephews, Matt and Ed Simpson

- The cascades

- Oscar-the-never-grouchy

- This is Oscar Knott, almost a year old. Just the sweetest, most cheery little boy you’d ever want to meet.

- Oscar with his mum, our niece Charlotte Knott, daughter of Roger’s sister Hazel.

- Charlotte and Oscar

- Roger with his mum and dad.

- Me with my parents -in-law, Ron and Margaret Warburton.